As I pack my bags for the American Planning Association’s 2023 National Planning Conference, happening this weekend in Philadelphia, I’m reflecting on my time at last year’s event in San Diego. I had submitted three session proposals, hoping one would stick the landing…much to my surprise, all three were selected. I felt so honored, but the result was a whirlwind weekend and—as evidenced by the fact that it has taken a year to share my presentations—I’ve only just recovered.

Better late than never; I don’t want to miss an opportunity to talk about the importance of planning and designing for well-being.

Of my three presentations at NPC22, I was most pleased to share my research alongside one of the most celebrated and internationally-recognized urban thinkers, Mitchell Silver, FAICP. Together, in our session entitled “Happy and Inclusive: Planning for Joy and Healing”, we called upon planners to create spaces that foster reflection, healing, and joy in the wake of a global pandemic and racial unrest.

Here’s why.

Today’s Intersecting Crises

Our lives are being disrupted in new and more significant ways seemingly every day. We find ourselves amidst intersecting crises: political polarization and turbulence, police murders of Black and Brown people, social fragmentation/civil unrest, and an ongoing global pandemic. Planners across the globe have been taking part in efforts to stir recovery—and a key component of recovery is that it must include joy and healing.

The pursuit of happiness has been beyond the reach for most of our Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) brothers and sisters. As equity scientist Dr. Lawrence T. Brown has explained, despite the ending of chattel slavery years ago, “Black communities have been subjected to unrelenting and ongoing historical trauma” (Brown, 2021). This “pre-existing pandemic”, as Dr. Brown calls it, has created conditions in BIPOC communities which threatened the health and well-being of their members, and this vulnerability had only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic, social, and political aftermath.

As urbanists are now saying, given that Planning 1.0 was rooted in public health from a physical wellness perspective (a point that my session co-presenter, Mitchell Silver, FAICP, has often made), Planning 2.0 will be guided by an understanding of the psychological responses we have to place (Hollander, 2022).

In all my roles, my work is driven by my mission. I work to create spaces and places throughout the world that foster greater mental health and emotional well-being by translating the science of happiness into planning practice.

History of Happiness Thinking:

Humanity’s history with happiness has roots in the Ancient insights of Aristotle, Confucius, and Buddha, and societies have pursued the concept ever since. The Ancient Greeks separated happiness into two categories: Hedonia (which can be summed up as good feelings) and Eudaimonia (which translates to “good spirit” and which Aristotle equated with a fulfilled life, or the good life). So, for as long as we can remember, the pursuit of happiness has been a key purpose of our existence.

In America, the “land of opportunity,” we had taken pride in offering people the chance to live the American Dream, promising happiness and the good life. Our U.S. Constitution even has clear eudaimonic principles, as it was written to protect our “unalienable Rights” of Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Unfortunately, by many accounts, we’ve missed the mark.

AICP Outlines our Responsibility

Now, speaking of “land of opportunity”, that’s where you and I, as professionals who shape the world, come in. Every planner I’ve encountered has pursued this line of work with some sort of drive to make the world a better, happier place.

Lest we lose sight of that initial resolution, the AICP Code of Ethics reminds us that we planners “have a special responsibility to serve the public interest, expand choice and opportunity…and plan for the needs of the disadvantaged…”

Currently, a big missing piece to this puzzle is fostering joy and happiness, which admittedly has been perceived as an intangible goal for many years. If we did a broad-brush analysis of our planning reports, urban design projects, etc. from the past decade, while we might be able to conclude that community happiness is an objective of our work—and some of our strategies indeed result in greater happiness—we’d see limited examples of projects where happiness was identified as the key strategy or driver. While we have Economic Development Strategic Plans, Transit Studies, Resiliency Plans … where are the “Neighborhood Well-being Assessments”, the “Community Happiness Action Plans,” or the “Citywide Happiness Initiatives”? Who’s tracking happiness levels year-over-year at the local level? I’ve looked, and it’s been hard to find much in this arena. From my investigations, I’ve concluded that communities who are prioritizing happiness as a key community health strategy are few and far between.

To be fair, I can understand how “happiness” might seem like a fuzzy concept. Yet, perhaps it’s not as fuzzy as we might initially assume.

The Science of Happiness

Colloquially, I’m using the word happiness, but the more precise term when it comes to measuring and monitoring this experience is “Subjective Well-being” (SWB). As Lomas, et al., noted in the 2022 World Happiness Report, “[s]cholarly understanding of happiness continues to advance with every passing year, with new ideas and insights constantly emerging” (Helliwell, et al., 2022). Indeed, happiness can be reliably measured, and it’s likely a better gauge of progress than our typical measures.

Indeed, as it turns out, it’s not only possible to track happiness, but it may also be a more meaningful measure of progress to members of our communities. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been the most widely-used measure of economic progress—often “treated as if it were a measure of economic well-being”—but confusing GDP for well-being misrepresents how well people are truly faring, which risks misleading policy decisions (Stiglitz, Sen, & Fitoussi, 2009).

Thanks in large part to the growing availability of happiness data and a “strong public appetite for this conception of progress,” thinking has evolved as researchers, organizations, institutions, and governments are now crafting new sets of indicators which can measure individual reports of happiness and satisfaction with life.

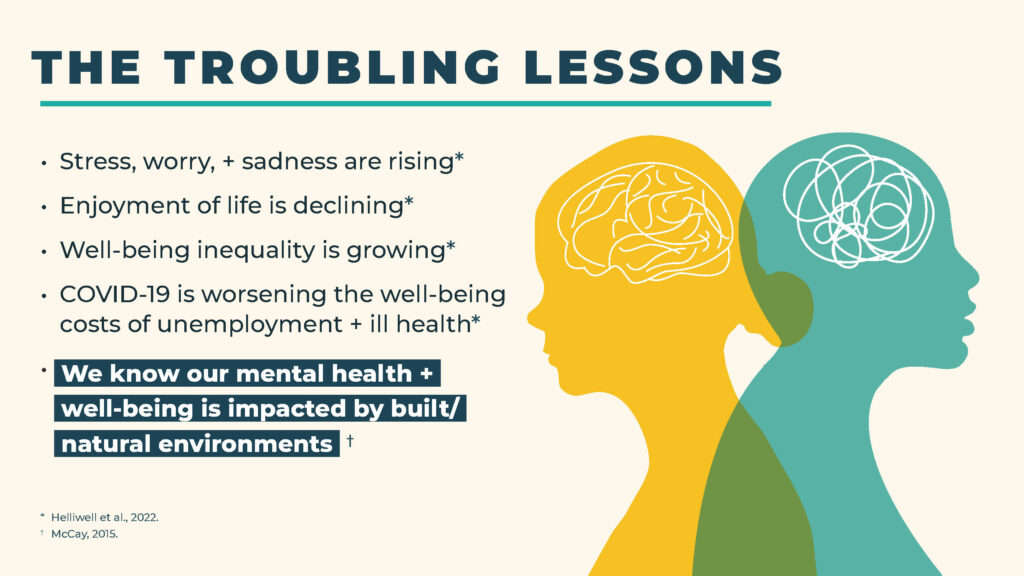

There’s Work to be Done

Perhaps the “… most important reason for the new and burgeoning interest in happiness,” explains the Global Happiness and Well-being Policy Report, “is that it’s possible to do something about it!” (Global Council for Happiness and Well-being, 2019, p. 5).

And planners ought to do something.

Relatively new areas of research are helping us to measure the psychophysiological reactions happening in our bodies when we navigate through the built environment. Sometimes this is a brief, momentary reaction that lasts only for the duration of exposure (think: cluttered rooms/spaces, traffic jams, loud street corners, etc.), and we may or may not be aware of the effect of these spaces. But in other instances, our environments can contribute to lasting, chronic health issues from impacts on our minds and bodies that we’re likely not consciously aware of.

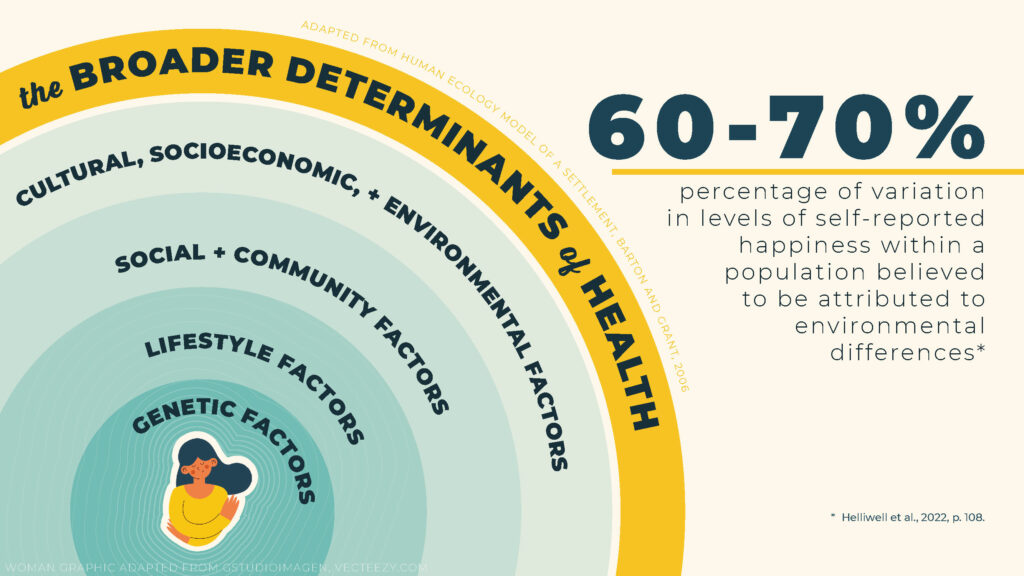

In short, well-being is tied to place. While there’s some degree of personal happiness that is informed by our genetics, researchers agree that there is quite a bit of wiggle room, and that our happiness is further influenced not only by our personal choices and behaviors, but also by our environments and experiences. Which might imply that our cities and neighborhoods could be a first-order of defense.

When it comes to mental ill-being, the common argument was that happiness is not a public nor political matter, that well-being lives in the private sphere. “But the fact is that every decision made in public life … has some effect on our physical and social environments, and thus some effect on our well-being” (Roberts, 2011).

This is a Planning Solution

As stewards of the built and social environments of our communities, it is our responsibility to acknowledge the significant capacity of place to either foster or diminish health and well-being. Whatever we can influence, we should.

A series of health and well-being measures called the “Social Determinants of Health (SDoH)” paint a picture of the economic, political, social vitality in our communities, and the relationships between these conditions and states of well-being may be bi-directional.

The fact that these measures perform worst in communities that have experienced discrimination, marginalization, and disinvestment alert us to the devastating feedback loop.

ZIP Code v. Genetic Code

We’ve all heard it explained before that “our ZIP Codes are better predictors of health than our genetic codes.” American biostatistician Dr. Melody Goodman said this when addressing a group of students from Harvard’s School of Public Health, where she explained that the odds of her own success in life were stacked against her simply because she, a Black woman, grew up in a family experiencing poverty in New York City. Dr. Goodman studies and addresses health disparities among factors of race, privilege, discrimination, and community engagement.

We see this story evidenced most clearly with physical health data. The pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color—but Black and Brown communities have long been dealing with epidemics of inequalities.

Communities are dealing with the lasting impacts of harmful planning and community development practices of yesteryear, including redlining; Greenlining; predatory lending; restrictive covenants; inequitable allocation of capital improvements; and displacement, gentrification, and the disintegration of neighborhoods under the guise of urban renewal.

Planning decisions of the past have directly contributed to the harming of Black and Brown communities, which can be attributed to the disproportionate suffering in those communities of the impacts from fluctuations in the strength of the national economy, racial policing, pandemics, and the like.

Past decisions have created physical, social, and economic challenges in our communities that have led to experiences of trauma among community members—traumas that influence how people function in their communities, often leading to new challenges to which prompt planners to react without adequate understanding of the big picture.

Without intervention, this will be a never-ending vicious cycle. But if we think of this with an optimistic bias, we can see the potential, instead, for a virtuous cycle.

The Place-Equity-Well-being Connection

If well-being is an equity problem, we might also see well-being as a potential means to advance equity in our communities. The AICP Code of Ethics again reminds us that we must “recognize our unique responsibility to eliminate historic patterns of inequity tied to planning decisions represented in documents such as zoning ordinance and land use plans” (§A.3(a)).

As already mentioned, a significant portion of our well-being can be attributed to our environments, and given that our planning decisions have shaped communities in such a way as to create roadblocks to happiness, we begin to see the interconnectedness of equity, place, and well-being. Inequalities in the built environment underlie and exacerbate health and well-being challenges.

Our communities need to heal—not just from the damage inflicted by past planning decisions, but from all manners of trauma. As planners, we need to be aware of our community’s well-being, we need to redress past harm, and at the same time we need to create the conditions that can foster healing and joy and happiness. We need to embrace the promotion of health and happiness as primary drivers of our work, which we can advance through policy, design, and research strategies.

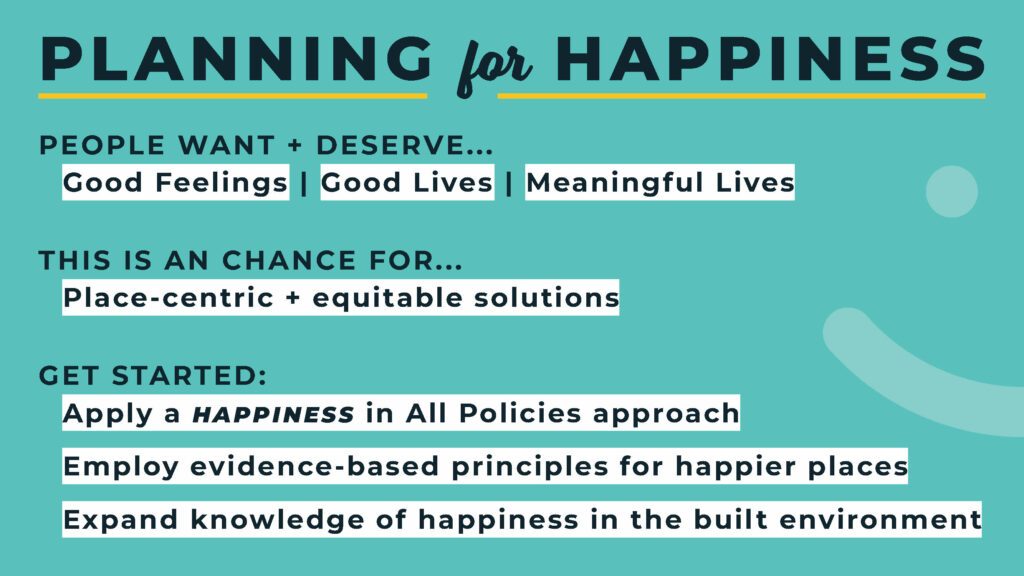

Policy Strategies

To foster joy and healing, we need to apply a Well-being in All Policies (WiAP) approach, incorporate well-being outcomes into our priorities, and use the science of well-being to inform government decision making.

Design/Practice Strategies

To foster joy and healing, we need to incorporate a trauma-informed and social-connection-centered process and shape/design/plan happy places by employing evidence-based design/planning principles.

Research Strategies

To foster joy and healing, we need to continue supporting and sharing research that explores community well-being. We need to collect local data about well-being to track progress over time.

Call-to-Action

I’m calling planners to action as I invite my peers to join me in bringing well-being to the forefront of planning decisions in our communities and prioritize well-being and healing initiatives in the communities who need and deserve it the most.

Let’s revolutionize the profession, and usher in a new era of well-being informed communities.

Citations

American Institute of Certified Planners. (2021). AICP Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com/document/add38c5d-71d4-4915-92d6-650140adf7fbAICP-Code-of-Ethics-and-Professional-Conduct-2021.pdf

Global Council for Happiness and Well-being. (2019). Global Happiness and Well-being Policy Report 2019. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2018. Electronic. https://www.happinesscouncil.org/report/2019/global-happiness-and-well-being-policy-report

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., Sachs, J. D., De Neve, J.-E., Aknin, L. B., & Wang, S. (Eds.). (2022). World Happiness Report 2022. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Hollander, J. B. (Host). (2022). Public Health and Urban Planning 2.0 (No. 6) [Audio podcast episode]. In Cognitive Urbanism. https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/public-health-and-urban-planning-2-0/id1437332617?i=1000420458611

Roberts, D. (2011). Great places: turning from stuff to happiness. Retrieved fromhttps://grist.org/article/2011-05-24-great-places-turning-from-stuff-to-happiness/

Silver, M. (2012). Planners and public health professionals need to partner…again. North Carolina medical journal, 73(4), 290–296.