Do you love where you live? If you do, then I just have to ask . . .

“If you love it so much, why don’t you marry it?”

If you think my question is facetious, you might be surprised to learn that in 2011, over 2,000 people gathered together in Durham, North Carolina, to “Marry Durham” in what has been described as “the largest civic union in history” (Kageyama, 2011). On that day, their vows demonstrated a shared commitment to a community they all loved, with the ceremony itself serving to raise over $25,000 (well over double the event’s original goal) to support social services, community groups, and local causes in Durham.

Over 2000 people.

Raising over $25,000 in donations.

Showing up to demonstrate intense love for their community.

It makes you wonder: alongside walkability and livability indices, should we be considering measures of lovability when we shape our cities?

Place Lovability and Why it Matters

As far as I’m aware, no “lovability” indices exist . . . yet. But if one did, Durham would surely receive high marks.

While the Marry Durham event may have employed a truly out-of-the-ordinary technique to showcase their love of place, people around the world are equally in-love with their communities, demonstrating adoration for their hometowns via community campaigns, public art, local merchandise, festivals, and personalized expressions of their affection.

Place Attachment

In all of these examples, we’re observing expressions of “place attachment“–a theory which describes the cognitive-emotional bond people form with places where they live and spend time (Hidalgo and Hernandez, 2001; Giuliani and Feldman, 1993; Scannell & Gifford, 2014; Cross, 2015; et al.). Research suggests that place attachment is not only beneficial to communities, but it can also provide a boost to individual wellbeing.

If we think back to our basic understandings of wellbeing–recalling theories like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943) or the definitions of happiness and subjective wellbeing (see the earlier Defining Happiness post)–we recall that our state of wellbeing is layered, often evaluated both as a snapshot of both purpose and pleasure. Similarly, the benefits people derive from feelings of place attachment are also multi-dimensional.

Place attachment can be viewed in both functional and emotional dimensions. First, functional place attachment arises when a person feels their environment can sufficiently support their needs and contribute to their survival. In this case, place attachment fosters place dependence, defined as the “cognitive functional attachment that arises when a place provide the conditions required to meet an individual’s needs” (Vilarem, 2019). People need a sense that their environment can adequately support them and contribute to their ongoing survival. As an individual bonds to their place, this assurance can be received.

The second dimension of place attachment is largely emotional and typically grows over time as an individual becomes psychologically, socially, and emotionally connected to place. Through its functional dimension of place dependence, place attachment is tied to our basic survival, while forms of place attachment in the emotional dimension begin to contribute to our ‘thrival’. This sort of place attachment centers on theories place identity, or “the affective and symbolic importance given to a place as an individual becomes psychologically invested” (Vilarem, 2019). Place identity is continually developed as we get more invested in our communities and cultivate a sense of self that’s reflected in elements we find within our communities. Furthermore, as we actively participate in shaping our surroundings, we begin to align our space with our own personal goals, reaching closer toward a state of Eudaimonic happiness.

The Ingredients of a Lovable Place

As people develop feelings of place attachment, this can lead to a deeper sense of self, a strong sense of ownership tied to one’s community, and a sense of belonging and connection–all of which can, in turn, further reinforce place attachment.

Sense of Place/Identity

As you might imagine, it’s difficult to form an attachment to a place when that place lacks definition or points of pride. There must be a there there if you’re going to love “there”. Our spatial cognition provides a frame of reference for describing and isolating one place from the next. Sense of place can be created and reinforced through physical and programmatic interventions in the environment. Visual legibility, or the ease with which we can “read” an environment provides ease of spatial cognition and our initial understanding of a place. Places then develop personalities that are distinctly theirs through unique markers of identity (for example, placemaking features, community branding, geographic or cultural landmarks, etc.). Additional sensory stimuli of places with strong place attachment are congruent with the initial understanding of place and coherent with the ongoing representation of that identity, establishing continuity overtime, which should persist without significant disruption. Elements of culture are important features of place identity, and include, for instance, public art, relics of history, and storytelling (identity is not purely physical, and social narratives provide a more expansive understanding of place).

Sense of Self and Ownership

As people become connected with places, their sense of self can be reflected in the place identity. Much like our homes are manifestations of ourselves as individuals, our communities become a physical manifestation of our collective lives and stories (Keedwell, 2017). The more we feel connected to a place, the more it feels like an extension of ourselves and our personal territory, so we are likely to take ownership and get involved with ensuring its continuation.

The Social & Personal Experiences of Place

Research also shows that place attachment can foster and be fostered by our social and experiences. When we are a part of a community, we cultivate a sense of belonging and connection with our neighbors and fellow community members. Third spaces, or places that encourage communication and interaction through design features or site furniture (such as benches oriented toward one another), can facilitate social connection and a sense of attachment to the people in one’s community. Strong social ties boost feelings of being engaged, empowered, and a part of something larger than oneself.

To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.

Simone Weil

Meaning-Making in Place

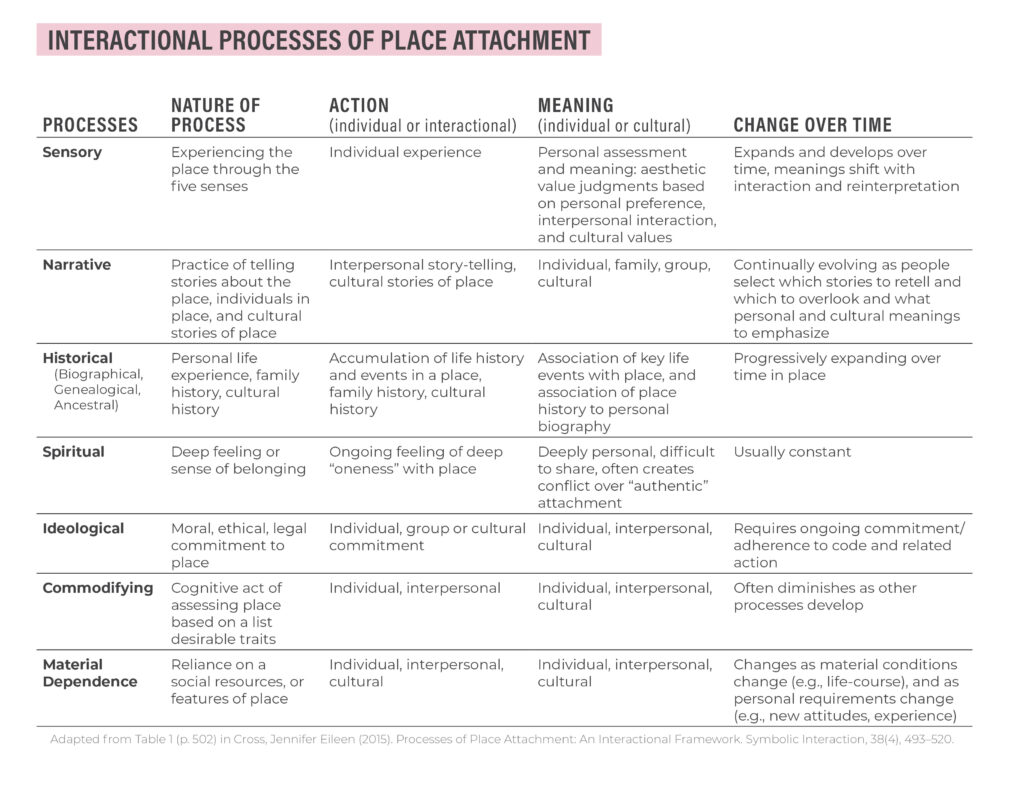

In addition to the qualities of place described above, there’s research to support a strong link between the degree to which we feel attached to a place and our level of engagement with, or contribution to shaping that place (Keedwell, 2017). In her work, Jennifer Eileen Cross describes place attachment as an interactional process in which people engage in meaning-making (2015). She proposes seven common ways in which people cultivate their relationships to place: (1) sensory, (2) narrative, (3) historical, (4) spiritual, (5) ideological, (6) commodifying, and (7) material dependence (see the included table).

As we engage in meaning-making with our surroundings, we begin to align place with our personal goals. So don’t assume that you’ll have to move to find that spark if you don’t love where you currently live. For anyone who feels that their flame with their community has either faded or never kindled much to begin with, there are some proven strategies to strengthen bonds and boost place attachment.

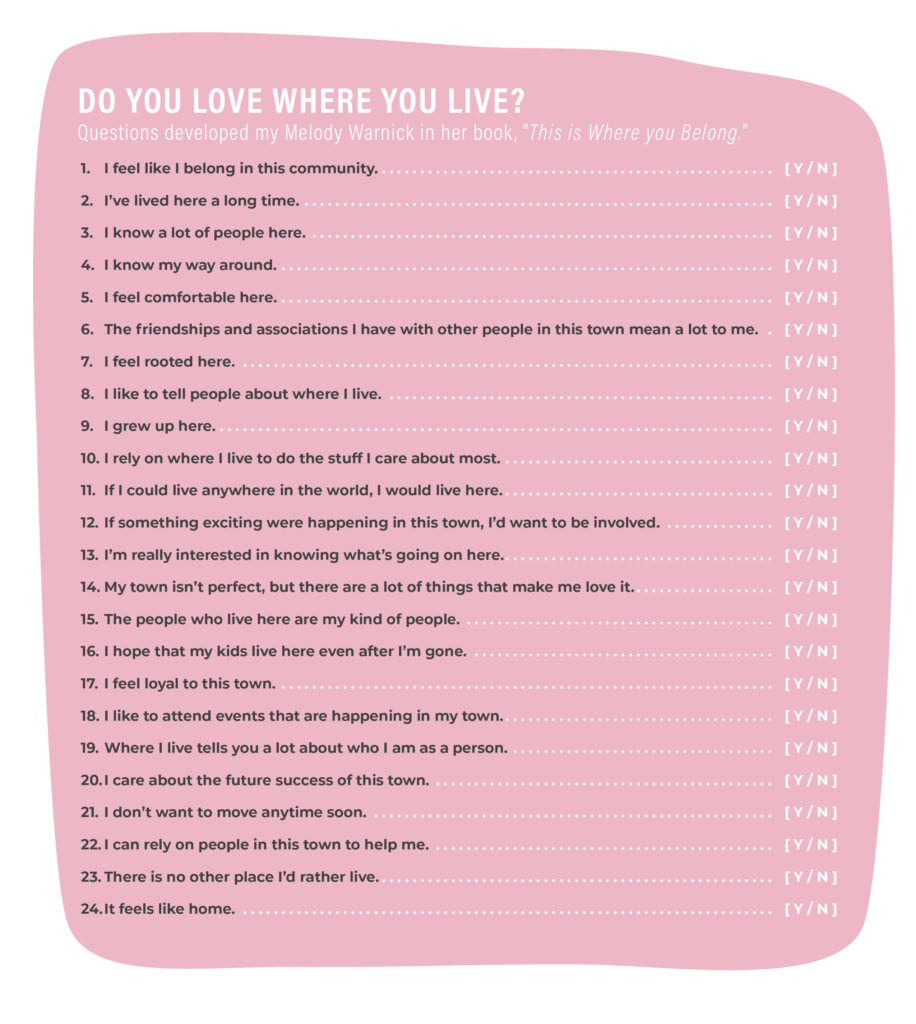

In her 2017 book, This is Where You Belong: the Art and Science of Loving the Place you Live, author Melody Warnick discusses strategies that are shown to help people establish roots where they are and show a little more love for their communities. She starts by providing a list of 24 yes-or-no questions to gauge your current level of place attachment.

Using your answers as a baseline, you can set out to engage in one of ten behaviors that will deepen your place attachment. These include:

- Walk more

- Buy local

- Get to know your neighbors

- Do fun stuff

- Explore nature

- Volunteer

- Eat local

- Become more political

- Create something new

- Stay loyal through hard times

The Places Where We Live Can be Places of Love

As we see, though our environments may create conditions that facilitate pace attachment, each individual has their own role to play in meaning-making and cultivating bonds with their community.

So, take a look at your own community. Are you in love? There’s no shame in answering “no”–but if that’s your answer, think about what you can bring to the table to show your community a little more love and, in turn, make your community a bit more lovable, too! This valentine’s day, if the love is fading, I encourage you to rekindle that flame!

Resources

Anderson, DL. (2011, March 23). Marry Durham. Indyweek. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://indyweek.com/news/marry-durham/

Ellard, C. (2015). Places of the heart: The psychogeography of everyday life. Bellevue Literary Press.

Bonaiuto, M., Mao, Y., Roberts, S., Psalti, A., Ariccio, S., Ganucci Cancellieri, U., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2016). Optimal Experience and Personal Growth: Flow and the Consolidation of Place Identity. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 1654. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01654

Cross, J.E. (2015). Processes of place attachment: an interactional framework. Symbolic Interaction, 38(4), 493–520. doi:10.1002/symb.198

Scannell, L. & Gifford, R. (2014). The Psychology of place attachment in Gifford (Ed.) Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practice (5th ed., pp. 272-300). Optimal Books.

Giuliani, M. V. & Feldman, R. (1993), Place attachment in a developmental and cultural context. Journal of Environmental

Psychology, 13, 267-274.

Hidalgo, M.C., & Hernandez, B. (2001). “Place attachment: conceptual and empirical questions.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 21(3):273–81.

Kageyama, P. (2011, November 30). For the Love of Cities [Video]. TEDxIowaCity Conference. Retreived from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6K7OKw_rSz0

Keedwell, P. (2017). Headspace: the psychology of city living. Aurum Press

Knight Foundation. (n.d.). Soul of the community. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://knightfoundation.org/sotc/

Loflin, K. (2012, August). Making the Case for Place: Dr. Katherine Loflin at TEDxSoCal [Video]. TEDxSoCal Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tjfp5yhO35o

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A Theory of human motivation. Originally Published in Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

Pasca, R. (2014). Person-Environment Fit Theory in Michalos, Alex C. (2014). Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (pp. 4776-4778). Dordrecht: Springer.

Vilarem, E. (2019). The Role of attachment in place-protective behaviours. Conscious Cities Anthology 2019: Science-Informed Architecture and Urbanism. Doi:10.33797/CCA19.01.11

Warnick, M. (2017). This is where you belong: The art and science of loving the place you live. Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.